“I hate rubrics!” The fact the statement was made with as much passion as I utter the words, ‘I hate spiders!’ left me more than a little curious. Unfortunately for me, there was no further explanation from that particular Facebook poster, so I was left to wonder why. (Unlike you who will totally understand that the work of spiders can be done by thousands of other crawly things and therefore there is no real need for them to exist. Sorry…I just had to get that out there…I digress…)

My curiosity led to google (of course) where I got nearly 5 million answers as to why this might be. Reminder to self:

Another Reminder to Self - Assume Nothing

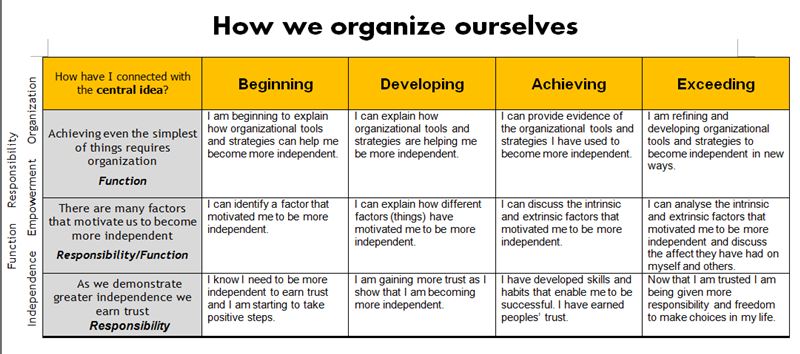

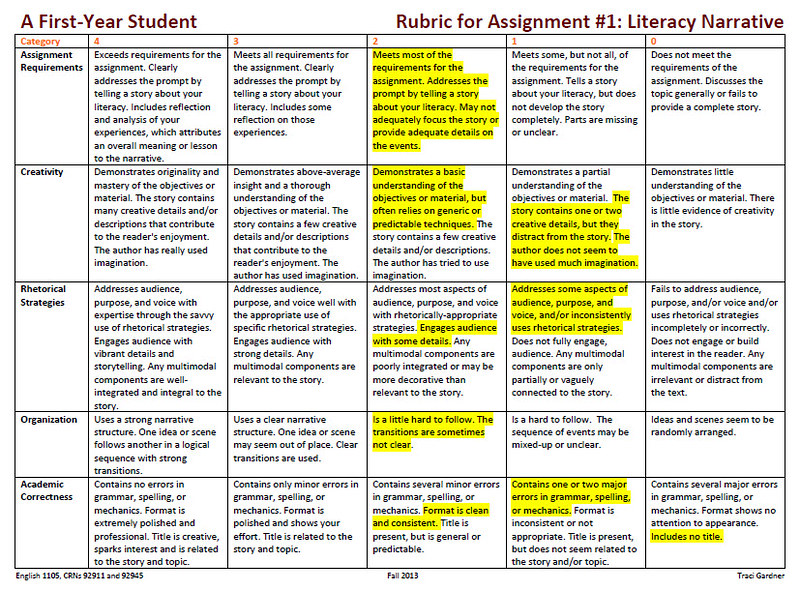

Before I launch into the whys and wherefores of rubrics, let’s define what we are talking about. (Feel free to skip ahead if you’re already familiar with the term.) I learned the word ‘rubric’ after during my teacher training as it’s a term in common usage in North America, but maybe not so much in other places. When I finally saw one, I realised it was what we in the UK would simply call an ‘assessment grid’ – basically a table of criteria that you’d expect to see in a student’s piece of work with descriptors at various levels. Here are a couple of visuals.

If neither of these look like a familiar assessment tool, no problem. Read on to learn more about how they can help – or hinder – your students’ understanding of what they are aiming for.

Let’s start with some common issues teachers have with rubrics.

Why the Haters?

As with anything in teaching, if rubrics don’t offer benefits to make them worth the time spent making them they’ll soon be discarded. Some of the reasons people in my online teacher groups avoid rubrics:

- they oversimplify and don’t capture nuance

- students don’t look at them

- the language in them is inaccessible

- the bulk of most rubrics focuses on what students didn’t achieve rather recognising what they did well

So, what to do? Throw out rubrics once and for all or think again? Unsurprisingly, I’m here to advocate for a rethink because every single objection I read about them has a response. More than that though, I believe rubrics can increase equity in the classroom, and here’s how.

My Plan for Fixing Rubrics

Although my plan takes a bit of time and effort, it’s worth it – create rubrics with students. ‘Whaaaat?’ I hear some of you say. ‘Ain’t nobody got time for that!’ but…brace for a hard truth…if you don’t have time to start making assessments clear to students, you don’t have time to be the teacher your students need. And remember – once you have a clear student-friendly rubric, you can re-use it year-after-year.

Also…you don’t need to create rubrics from scratch! You can take an existing rubric, and ask students what could be clearer. If students are reluctant to admit their confusion, ask them to work in pairs or small groups to paraphrase the rubric for younger learners. This will highlight where the work needs to be done as you will see their misinterpretations. From there, work together to replace confusing language with terms they understand.

Replacing language is a start, but if you want to students deeply and unquestionably understand what they are being asked to do, go with co-constructing from scratch.

When you co-design rubrics when you can, you’ll build up a collection that you can tweak and re-use every year. However, there will some assignments where co-constructing rubrics with students is a priority.

How will you know which ones they are?

Easy! They’ll be the assignments where students repeatedly seem to miss the point – the ones where you think you’ve nailed the explanatory lesson year-on-year and yet you are utterly underwhelmed by your students’ submissions. They leave you feeling rather…

Now that we’ve identified the why and what, let’s see how we can go about creating rubrics that really do lead to better student outcomes.

Step 1 - Learn from the Best

It really doesn’t matter what subject you teach. Whatever your students are aiming to emulate, they need examples or mentor texts. Use samples from previous years’ students. If you don’t have those, make one as a model. If you can’t do that – for whatever reason – find examples ‘in the wild.’ If none of these 3 options work for you, perhaps reconsider your assessment. It’s fine to create new forms of media, but if it is impossible to find something relatable that supports their learning, you may be asking students to perform beyond their Zones of Proximal Development.

Step 2 - Deconstruct Models

Before we continue – a caveat. This might seem obvious to avoid, but experience tells me that it still happens in classrooms. Don’t include skills and knowledge that haven’t been explicitly taught or reviewed before the assessment. This can be a result of making assumptions about students’ previous learning experiences, and it will only widen the gaps between those who know and those who don’t know. Level the playing field by ensuring all essential skills have been covered intentionally and thoroughly.

Provide students with examples of the task they are aiming for, preferably not from your current learners unless you are sure this would not be uncomfortable for them. These examples should range in quality so students can see what to avoid as well as what to aim for.

One method I use is a take on the gallery walk. I create stations according to the number of examples (mentor texts) I have.

For One Mentor Text

Create stations around the room (or on slides) with the mentor text at each station. Create a different prompt for each station that will guide students to notice important features. For example, if I was doing narrative writing, example questions might be:

- How effective is the opening in grabbing the reader’s attention?

- To what extent does the writer use figurative language effectively?

- Why might this writing be considered (not) well-organised?

The questions will depend on the skills I’ve noticed my students need to work on and will be connected to our learning goals for that unit.

For Multiple Mentor Texts

If I have more than 1 mentor text, students will respond to the same prompts for each one. Again, I will tailor the prompts to what it is I feel students need to notice, but some examples might be:

- What makes this writing effective?

- What might be improved in this writing?

- What techniques do you see that could you imitate in your own writing?

These ideas can be tailored to your own approach and the needs of your class, but hopefully I’ve illustrated a couple of options.

Step 3 - Construct the Rubric Together

Dependent on time, you can start students off with a blank grid or you could pre-populate it with any of the following:

- the learning standards you are aiming for in student-friendly language

- the criteria you want students to aim for (and then you co-construct the descriptions)

- descriptors for each level taken from the gallery walk activity and using the students’ own words

Below is an example of a blank rubric template I used with my students from 2012 before they did a performance. The resulting rubric is below. (Carla was a student in our class who brought up a recent performance her cousin had been in. Clearly, Carla hadn’t enjoyed the experience!)

The process of co-construction can look different at different times of the year. Some options:

- students work in teams to populate one column or row; they then peer edit contributions until they agree on the descriptors

- teacher (or a confident) student leads a whole-class discussion on what should go in each section; scribe enters the agreed language

- teams populate the whole rubric, then come together to negotiate a final version

No matter which method you choose, it is likely you will have to edit the final version to tidy it up. However, minimal editing should come from the teacher in terms of the actual ideas and concepts the rubric communicates.

Single-Point Rubric

When students are ready, you might want to simplify the process by producing a single-point rubric. I have found that students need the scaffolding provided in a multi-tiered rubric when the task is more complex or it is new to the students. However, as the year goes on and students become more adept at creating their own rubrics and understanding expectations, I do use single-point rubrics more often. The great Jennifer Gonzalez tells you all you need to know on her blog here.

Further Reading

If you’d like to explore this topic a bit more, here are a couple of resources I find helpful in developing my thinking and practice:

If you only try it once, at least you’ll be able to make an informed decision about whether co-constructing rubrics works for you and your students. Let us know if the Diversity in Mind community support you further or leave your own tweaks and ideas in the comments below.

We’ve got this!