As much as we’d love to diversify our curriculum to have more of a balance of voices from different cultures, it’s not always within our power to do so. Even if it is, there are sometimes good reasons for continuing to teach ‘classic’ texts.

Not all teachers agree. Indeed, I was challenged in an equity-focused teacher group for suggesting it might be OK to continue teaching what they referred to as ‘male, pale, and stale’ texts if it is done with diversity in mind. Some feel that traditional classroom libraries need a complete overhaul whereby all ‘classics’ are completely replaced with diverse voices. I would argue that ‘diverse voices’ includes the dominant majority, but of course there needs to be a consideration of what constitutes a ‘classic’ and there must be representation across a range of cultures. It’s an argument I continue to think about and discuss.

One of the reasons traditional texts might be useful is to encourage students’ critical literacy. I mean, if you’re seeking texts that allow an exploration of power issues such as racism, oppression, and classism, even younger students will find the English canon to be rich grounds for hunting.

Teaching reading with a critical lens empowers students to interrogate existing power structures and the status quo. Once they begin this journey, their eyes are opened and they can start to challenge systemic inequalities; the ‘challenge’ might be as straightforward as defending a position in a classroom debate, but of course we hope that as they grow, mature and influence others the ripples will cause change for the better. In this post, we’ll explore a few ideas for broadening students’ exposure to diverse voices, perspectives, and cultures while teaching Shakespeare.

Make Time To Diversify

While it seems fairly common practice for teachers to select key scenes from Shakespeare and focus solely on these, I am still a fan of having students get the complete story from beginning to end rather than seeing literature as disconnected passages with no overall ‘shape’. With Shakespeare, whole text study can be very slow going due to the complex language and many unfamiliar references. Luckily, I found a solution many years ago in the form of the UK’s Shakespeare Schools Festival play scripts. They are abridged versions of the play that keep the original language, but cut the performance down to around 30 minutes. I’ve had great success with these with students from 9-18. Unfortunately, at the time of writing, I can’t seem to find the actual scripts on their site but I’ll email them and update here when I get a response.

At the same time, I’m pretty sure you can find something from these resources to meet your needs:

- 30 Minute Shakespeare (original language, paid, from around USD$12.95)

- Lazy Bee Scripts (original language & adaptations, 30-40 minutes, from around GBP£18)

- Adapted Scripts from Richard Burbage (free)

- Compact Shakespeare (abridgements & adaptations, free)

- Wichita Shakespeare Company (abridgements, free)

- Drama Resource (adaptations, free)

Added to this raft of choices, you can have students watch a performance of the play in question. Even though they are quite old now, Shakespeare’s Animated Tales somehow always gets a good reception from my students. Below is the embedded playlist on Youtube. Of course, links may expire but you can always find another version with a quick search. Click here to bookmark the playlist.

One more thing – taking a critical approach (which always involves an exploration of power relationships) does not require late nights of planning. Melissa of the Reading and Writing Haven describes a simple approach she uses with her students here. If you do not have the support of your librarian, contact me or join our Facebook group where you will find people only too happy to help.

So, unless your school insists that you study every line of your mandated Shakespeare play, why not create some space to put some of the following ideas into practice to diversify your unit?

Connect Shakespeare With Modern Times

Although reflective teachers at least question the relevance of the Bard in our classrooms, it’s difficult to find a course on ‘English Literature’ that doesn’t include some reference to Shakespeare. Thankfully his texts are rich in opportunities for critical readings that expose and explore issues that we still face today. Read on for connections you can encourage your students to appreciate.

Othello

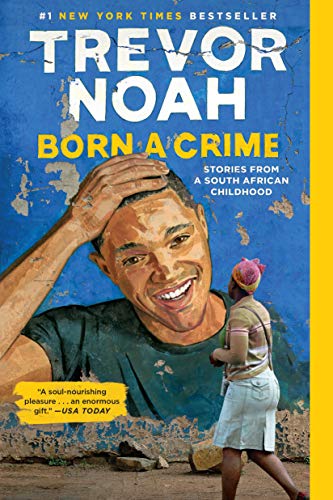

Most units on Othello cannot help but at least touch on racism. However, we can go much deeper than a single lesson on racial slurs or Elizabethan attitudes; the play facilitates rich discussions on the meaning and appearance of overt, internalised, and systemic racism. Looking at these in both Shakespeare’s time and today will help students understand the evolution of racism as a concept and social issue. It could also be paired with South African Trevor Noah’s Born a Crime alongside examining how race is a social construct rather than a scientific taxonomy.

Here are some ideas of how you might start a conversation around race with your students:

- Toolkit for “Excerpt: Getting Real About Race” (Learning for Justice)

- The Definition of Race Lesson Plan

A couple of articles you might find useful for your own, or older students’, pre-reading:

The free reading-focused site, CommonLit, has some text pairings that will guide older teens to connecting issues and themes within the play to the wider world. Even if you don’t use the actual texts, the topics are worth exploring. You could discuss what these topics look like in your own society and cultures, before widening the perspective to compare with others:

- the nature of love

- the psychology behind violence and ‘bad’ choices

- vulnerability and love

- changing perceptions of marriage

- (in)equality between genders

Finally, the document below offers 4 critiques of Othello. Use these to track attitudes over time toward the play, as well as the societal perspectives they may offer.

The Tempest

The Tempest connects directly with issues of colonialism. While this may be lightly skipped over, it is the perfect opportunity to explore the lasting impact of colonisation on both the colonisers and the colonised. Fortunately, the free site CommonLit already has a number of shorter texts that can be paired with The Tempest to explore this and other themes. Access it here.

Although the texts on CommonLit are tagged as 11th/12th grade (17-18-year-olds), I have taught The Tempest to 13/14-year-olds in the UK. In fact, there are classrooms in the UK where it is taught to much younger students.

Whatever the age of your students, here are some articles you might find useful in preparing to look at the play through the lens of colonisation and power:

The Merchant of Venice

The Merchant of Venice was a core text in my A-Level course as I prepared for university. I remember doing the usual character, plot, theme study but I don’t recall being aware of any debate around its appropriateness on a literature course.

Over four hundred years after The Merchant of Venice was first written, the debate rages on about Shakespeare’s intentions regarding the character of Shylock, whether the play is anti-Semitic or a criticism of the Christian anti-Semitism of Shakespeare’s time, and even whether the play should be taught in schools. (Kupfer, C., 2009)

There are those who would prefer we simply removed the play from our curriculum altogether and they make strong arguments, such as this one. If it is to remain in our classrooms, we have to be intentional about why and how we are teaching it, especially if we have Jewish community members in our midst. Reflecting on Kupfer’s quote above, examining the debate and different perspectives on antisemitism can only lead students to be better critical thinkers and literary analysts as they consider multiple perspectives and come to well-informed conclusions.

If our teen exploration of the play had been through a critical lens, it would have been so much richer and deeper. Given my country (Northern Ireland) had a negligible (and invisible) Jewish population, I knew very little about their history but it is such an important case study because it might be the oldest form of religious and cultural discrimination to still exist. Growing up with The Troubles, what great discussions we could have had about discrimination and hatred. The play would have been more relevant to our lived experience and we would have had an expanded vocabulary and conceptual understanding of an issue on our doorsteps. What parallels might we have drawn between attitudes to ‘the other side’ from Shylock’s vital speech?

Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions? Fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that.

A critical reading of the play could be the difference between a response like this and a response like this. Having both perspectives in the classroom may have value, but if students only ever explore Shylock as a villain, what a missed opportunity for some important learning!

To prepare for teaching this play, Sparknotes has a brief introduction to Antisemitism in Renaissance England. The Anti-Defamation League (ADL) has produced a guide for educators exploring antisemitism in the play. You can view it below or download it here.

Romeo and Juliet

If you’d like a deeper dive into this Shakespeare play, hop over to Danielle’s blog (Nouvelle ELA – I’m a die hard fan of everything she does) to see how she brings in different voices and perspectives with Romeo and Juliet. Read her brilliant thoughts here.

Other Romeo and Juliet ideas can be found in this post about bringing the play together with The Hate U Give.

If you’d like to try out a podcast, this NPR episode on a Rwandan Romeo and Juliet soap opera is a fascinating listen and highlights – again – the universality of destructive discrimination. This would be suitable for older students as it’s 50 minutes (although you could select extracts for a shorter activity). Provide students with some guiding questions or give them this free podcast organiser to complete as – or after – they listen. Filling in the organiser could be a precursor to a Socratic seminar or other class discussion.

Gender Roles

The Merchant of Venice includes some cross-dressing which links it to several other plays including Twelfth Night and The Taming of the Shrew. Gender is a topic Shakespeare explored often and for good reason. Some questions your students might ask as they explore these texts are:

- Who swaps gender roles?

- Why is this gender swapping seen as advantageous or useful?

- How is gender related to power in the play? Does moving between different gender roles empower or disempower?

- What does that say about the society in which these events take place?

- How do these aspects compare to our society?

- Given the absence of female actresses in Shakespeare’s day, how might this gender-swapping impact performances of the play?

Here are some resources you might dip into as you prepare this critical lens for looking at Shakespeare’s works:

- Lesson Plans from The Globe (search for ‘gender’)

- Gender Roles in Shakespeare (download the videos if they don’t stream in your location)

- The Role of Women in Shakespeare’s Plays (with great links under the article)

Know Better, Do Better

My own experiences with presenting Shakespeare have certainly involved monocultural approaches and narrow perspectives, but – as Maya Angelou reminds us – once we know better, we can do better. Wherever you are on this journey is where you need to be. To keep moving forward use the ideas on this page as a starting point, or share your own in the comments.

Remember, you don’t have to do it alone – our Facebook group is always available and you can reach out any time.

Critical approaches to Shakespearean texts that deepen their relevance for our learners?

We’ve got this!

Sources